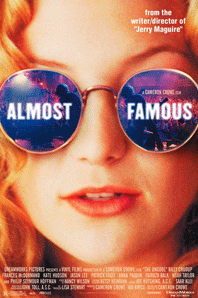

Cameron Crowe is one of the few screenwriters in Hollywood who has a voice (or, some might say, is one of the few allowed to have a voice). Voice is just one of the elements of craft that makes Almost Famous such a good film. What is even rarer in Hollywood is a film about how a writer came to find his voice. And that is what makes this such a valuable film for a screenwriter to study.

Cameron Crowe is one of the few screenwriters in Hollywood who has a voice (or, some might say, is one of the few allowed to have a voice). Voice is just one of the elements of craft that makes Almost Famous such a good film. What is even rarer in Hollywood is a film about how a writer came to find his voice. And that is what makes this such a valuable film for a screenwriter to study.

Crowe has always been known for his dialogue, which is where voice in a writer is most easily heard. But he has also pulled strongly from his personal experiences, so his writing always feels authentic and original. Other writers simply write the straight, high-concept genre script that is very top-heavy and emotionally hollow.

Using his own life doesn’t just make the script original. It also gives it a strong foundation. So when Crowe applies storytelling techniques for flourish and surprise, they have greater emotional payoff. To this end, he grabs from rock and roll legends as well as from a number of film genres, including the autobiographical movie.

Almost Famous is an excellent example of a story form I refer to in the Myth class as the Personal Myth. In this form you turn yourself into a fictional character and send that character on a mythical journey. This journey doesn’t have to be fantastical, but the real events must have fantastical overtones and the character must undergo major, almost archetypal change. Hope and Glory is a brillaint example of this.

When this personal myth is wedded with tragedy you get a film like Cinema Paradiso. Almost Famous doesn’t have the scope or the remorse of Cinema Paradiso. But it does use a comic journey to show the hero undergoing a profound change. As he did inJerry Maguire, Crowe focuses on a guy who has to learn how to do something of quality with his life. In this case, by writing truthfully and well.

This is a rare need in Hollywood movies, and another expression of Crowe’s voice. In a world that values money and success, how do you become a person of substance? Crowe answers that question not by making his hero a rock artist, but by coming at rock and roll from the “enemy’s” point of view. William is a kid who has the rare opportunity to write about a band from the inside. So he has a better opportunity for telling the truth, but he also faces a bigger danger of falling in love with the fame, glamour and the coolness of the world he is writing about.

Crowe gives William an ally in this fight, legendary rock writer, Lester Bangs. Of course Lester has to be legendary, because he is going to warn William about what he will face when he goes into the hole. They will seduce you, Lester says, and you will write swill. William’s Mom, so uncool she’s cool, is another ally in William’s journey to living with substance.

Off William goes on his bus tour with the band. And right away he meets the sirens. The Bandaids are the groupies (as opposed to Mom, who is a Harpy), led by the infamous Penny Lane. The Beatles’s Penny Lane, of course, is the greatest evocation of utopia in rock history. With Penny, Crowe lays a love story over the personal myth form. She is the ultimate expression of the seduction of the rock world, with her Lolita looks and hunger, but also with her gentle soul.

Crowe makes her a very positive character, worthy of being any boy’s first love. She is not just a sexual, experienced older woman, which would have been the easy way to set up a seductive opponent for the young hero’s quest. But as fine as she is, William must get beyond her, at least as she is in her present state. This Penny Lane is a false utopia.

William must also avoid falling for the male model for how to live, in the form of the “older brother” character, rock guitarist Russell. Russell has real talent, notices William. This is mentioned in almost reverential terms, though we never see how Russell’s guitar-playing talent can have such a holy impact on our lives. (Of course, Joseph Conrad couldn’t show what “the horror” meant, either, so maybe I should cut Crowe some slack here). But the super-talented Russell also does drugs, he sleeps around on his wife, and he wants to hide the truth.

Being friends with this good-looking ladies man would be easy. But then William could not be true to the cause, the art form of rock and roll.

To show why rock is worthy of being a holy grail, Crowe grabs a technique from the musical. Movie musicals, now virtually extinct, are about creating a community through music. In Almost Famous, Crowe takes the musical trick of all the characters singing together – normally a very artificial moment – and makes it appear realistic (not really, but it’s close).

After the band has almost broken up, William, Penny and the band members are all sitting forlornly on the bus. Bernie Taupin’s/Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” comes on the radio and one by one they all join in. Unfortunately Crowe oversells the beat when William says he has to go home, and Penny responds, “You already are home.” But this moment is a physical way of showing the audience what it means to live a life of substance, what it means to be true to what an art form can do.

Crowe uses other story tricks as well. As in classic coming-of-age stories, the hero loses his virginity, becoming a man in the most literal way. But this kid does it with three women at once. How’s that for playing the fantastical element in a realistic journey. And since this is also a love story, Crowe has Penny give William a nod farewell as the other girls start to undress him. Sure, William may be losing his viginity with three women but he’d really prefer to be making love with Penny. In story terms, this is called having your cake and eating it too.

Crowe creates the battle scene by taking the rock and roll legend of the small plane crash, cause of so many tragic losses in rock history, and turning it on its head. As the plane in which everyone is riding seems to be going down, each person confesses his many moral indiscretions, moving to farcical proportions. Crowe finishes the scene with young William telling off the band for using Penny. William has been able to see the moral weaknesses of the rock way of life by how they have treated the girl he loves.

Crowe writes by telling real emotional life moments in a funny way. It’s a fabulous combination, even though it goes against conventional “high-concept” wisdom. Voice is very intoxicating, and when it is combined with twisted genre beats and good, old-fashioned story tricks it is irresistable. What a pleasant surprise that two of the best films of this year, and two of the best films ever about rock and roll – “Almost Famous” and “High Fidelity” – are above all movies with a unique writer’s voice.

Let’s keep those voices coming.